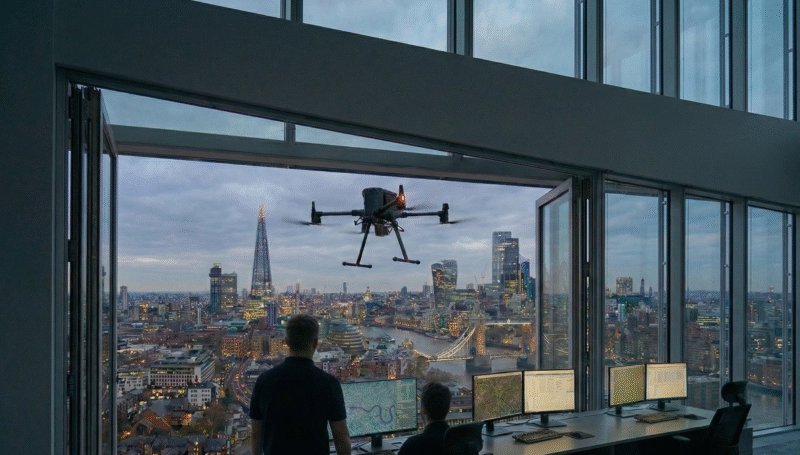

The United Kingdom stands on the precipice of a logistical revolution, one that promises to decouple the movement of goods from our congested, carbon-heavy road infrastructure. For the logistics founder, the autonomous drone represents a fundamental restructuring of the last-mile economy. The value proposition is seductive as delivery times are slashed from hours to minutes, orders of magnitude reduce carbon emissions, and the marginal cost of delivery defies traditional courier economics. However, the airspace above the British Isles, historically one of the most complex and strictly regulated in the world, is not a unified market ready for disruption.

As of recent times, the “wild west” era of experimentation has come to a close, replaced by a rigorous phase of professionalisation defined by safety cases, insurance mandates, and a strict roadmap toward Beyond Visual Line of Sight (BVLOS) operations.

Why “One-to-Many” is the Only Way

The foundational challenge you will face is not aerodynamic, but economic. The unit economics of drone delivery are very sensitive to regulatory constraints. In a traditional courier model, a single driver delivers hundreds of parcels a day. In the early stages of drone regulation, the requirement for a “one pilot to one drone” ratio effectively undermines the business case, rendering the cost per delivery exponentially higher than that of a van. The only path to profitability lies in the “one-to-many” model, where a single remote pilot oversees a fleet of 20 or more autonomous aircraft simultaneously. Consequently, your primary objective is not just building a drone that flies, but building a safety case that convinces the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) to permit that ratio. In this industry, your regulatory strategy is your business strategy.

This creates a “Valley of Death” for innovation between 2025 and 2027. While the technology for autonomous delivery is mature, the regulatory framework for routine access is still in the roadmap phase. Startups must survive a period of high cash burn, funding expensive operational safety cases and retaining qualified pilots while often restricted to low-volume trials. Surviving this period requires a nuanced understanding of funding mechanisms, such as the UKRI Future Flight Challenge, and the tactical use of the CAA’s Innovation Sandbox to secure temporary permissions that demonstrate capability without bankrupting the company.

The CAP 722 and the SORA Revolution

Unlike traditional aviation, where a certified plane can fly almost anywhere, drone regulation under CAP 722 is operation-centric. The risk is determined by the “ConOps” (Concept of Operations), which includes factors such as where you fly, how high you fly, and who is underneath you. The CAA divides airspace access into three categories, and choosing the wrong one can be fatal. The Open Category is effectively a trap for logistics companies as it restricts you to Visual Line of Sight (VLOS), meaning you can’t build a scalable network if your pilot has to stare at the drone. The Certified Category is reserved for high-risk operations, such as air taxis, and involves airline-level certification costs. Your operational home is the Specific Category, accessed via an Operational Authorisation (OA). This is the “golden ticket” that allows for BVLOS flights and operations over populated areas.

To operate in the Specific Category, you must master the Specific Operations Risk Assessment (SORA). The process begins with your ConOps, which defines your “Operational Volume” and the “Ground Risk Buffer”, , the area that could be impacted if the drone fails. From there, you determine your Ground Risk Class (GRC), which quantifies the danger to people on the ground. You can lower this score (and your regulatory burden) through strategic mitigations, such as flying over sheltered areas like railway lines, or technical mitigations like installing an independently validated parachute system. For a logistics drone over suburbia, a parachute is often the difference between approval and rejection.

Simultaneously, you must calculate the Air Risk Class (ARC), which measures the risk of mid-air collision. To lower this, you need to demonstrate “Tactical Mitigation Performance Requirement” (TMPR) essentially, a Detect and Avoid (DAA) system. In BVLOS operations, where the pilot cannot see the sky, electronic DAA systems must replace the human eye’s ability to see. Your combined GRC and ARC scores generate a Specific Assurance and Integrity Level (SAIL) score ranging from I to VI. Innovative startups design their operations to stay in the SAIL II-III range, as a SAIL IV operation can cost ten times more to approve and insure.

The 2027 Roadmap and “Atypical” Shortcuts

In October 2025, the CAA published the Future of Flight with the BVLOS Roadmap, setting a target for routine BVLOS operations in non-segregated airspace by 2027. But you don’t have to wait until then. The roadmap outlines “Atypical Air Environments” (AAE) as a pathway currently available. These are areas where manned aircraft are statistically unlikely to be found, such as very low-level flights directly above power lines, rivers, or railways. This is the “low-hanging fruit” for startups. By utilising AAEs, companies like Apian (delivering medical samples along the Thames) and Skyports (flying to offshore wind farms) are launching commercial services today without waiting for the development of complex urban airspace integration technologies.

For those targeting the urban “last mile,” the challenge is more complex. The airspace is cluttered, requiring high-precision navigation and Unified Traffic Management (UTM), a digital air traffic control system. The UK is currently pursuing a “federated” UTM model, where private providers connect to a government backend. However, reliance on third-party UTM providers introduces risk because if your provider fails, your fleet is grounded. Furthermore, the CAA is phasing in strict mandates for Electronic Conspicuity (EC). By 2028, almost all drones will need to broadcast their location to share the sky safely. The industry is currently debating whether to use ADS-B (the aviation standard) or mobile network-based Remote ID. Still, startups must ensure their hardware is “EC-ready” to avoid obsolescence.

The Hidden Costs of Insurance and Compliance

Founders often model the cost of the drone and the pilot, but underestimate the “burn rate” of compliance. Beyond the CAA fees, which can run into the thousands for complex applications, insurance acts as a de facto regulator. Under Regulation (EC) 785/2004, liability is calculated in Special Drawing Rights (SDRs). While the statutory minimum might be around £780,000, commercial clients and local councils will often demand £5 million to £10 million in public liability cover. Crucially, this regulation forces you to hold “War, Terrorism, Hijacking, and Sabotage” cover. It might seem absurd for a 5kg delivery drone to need war insurance, but without it, your operation is illegal. Insurers will audit your flight logs and maintenance records as strictly as the CAA, meaning a single claim can spike premiums for your entire fleet.

Social License for Noise and Privacy

Finally, your license to operate depends on the public. Noise is the most significant driver of complaints, specifically the high-pitched “whine” of rotors, which is perceived as more annoying than traffic noise. Startups must design “noise abatement” flight paths that avoid hovering over housing clusters. On the legal front, a drone equipped with a camera is considered a flying surveillance device under the GDPR. You must conduct a Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA) and adhere to “Data Minimisation”, recording video only when necessary for safety. The Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) suggests innovative transparency measures, such as apps that let residents see who is flying over them, to maintain community trust.

The Path Forward

The era of the “drone cowboy” is over. The UK drone logistics sector is now a professional segment of the aviation industry. Successful startups will follow a phased approach, including “Crawling” with PDRA-01 authorisations to test tech in 2025, “Walking” with bespoke SORA approvals for low-risk Atypical Air Environments in 2026 and finally “Running” with routine BVLOS operations in integrated airspace by 2027. The winners won’t just be the ones with the best technology, but those who can master this complex regulatory dance, turning safety cases into commercial assets and regulatory constraints into competitive moats.