The European Commission has been caught up in a political storm after revealing its proposals to loosen some of the European Union’s most talked-about digital laws. Critics say the move risks undermining leadership in data protection and digital rights that has been sustained for years.

The package introduced on Wednesday as part of a bigger strategy to revive European innovation is the first substantial attempt to alleviate the bloc’s landmark data protection framework since the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) was enacted in 2018. The plans provoked at once the displeasure of privacy advocates, groups of the civil society, and some EU parliamentarians who accuse the Commission of surrendering to the pressure coming from Washington and Silicon Valley.

The proposed alterations regarding the use of personal data for AI training are at the heart of the dispute. Brussels intends to facilitate access to user information for companies—especially European AI developers—under a few conditions. According to the Commission, the existing constraints have hampered innovation, slowed down new product development, and put Europe at a disadvantage in the global competition.

One more aspect of the package would do away with the cookie banners that have become almost a fixture of the internet and are the people’s first point of contact on almost every website. According to the Commission, the current system has turned into a mere form-filling exercise that confuses users instead of protecting them. There is another proposal whereby companies will be allowed more room to process “pseudonymised” data, i.e., data that is not directly linked to a specific individual but is still about that person’s behavior.

Arguably, Brussels is also looking at deferring the implementation of certain provisions on high-risk AI systems as another very debatable point in the EU’s package of AI reforms. These regulations—planned to be enforced under the bloc’s AI legislation—were aimed at ensuring the provision of strict safeguards around sensitive uses like biometric identification, employment screening, and vital public services. A postponement of the enforcement will provide companies with extra time to get ready with the critics warning that it may delay the arrival of important protective measures.

Henna Virkkunen, the European Commissioner for technology, threw some light on the proposals, saying, “We must move from rule-making to innovation building.” She continued, “Our rules should not be a burden but the added value that we need.”

Her point, which was meant to comfort the tech industry in Europe by showing that Brussels is willing to make changes in the face of rapid technological development, did not have the desired effect of calming the uproar. Opponents of the Commission’s stance argue that the effectiveness of the EU’s digital framework has been largely due to the EU’s refusal to concede to lobbying pressure—one of the reasons why American tech giants, which have regularly challenged EU regulations in court, have been so unsuccessful.

Several of the most controversial points had already been softened by the time the leaked draft that prompted a strong protest in the early months of this year was made public. However, according to the privacy advocates, even the updated version signifies the EU’s disengagement from being a global standard-setter for data protection. A number of parliamentarians expressed their doubts about the changes in the privacy of their constituents and hinted that the modifications could give the impression that Europe is willing to trade off rights for industrial competitiveness.

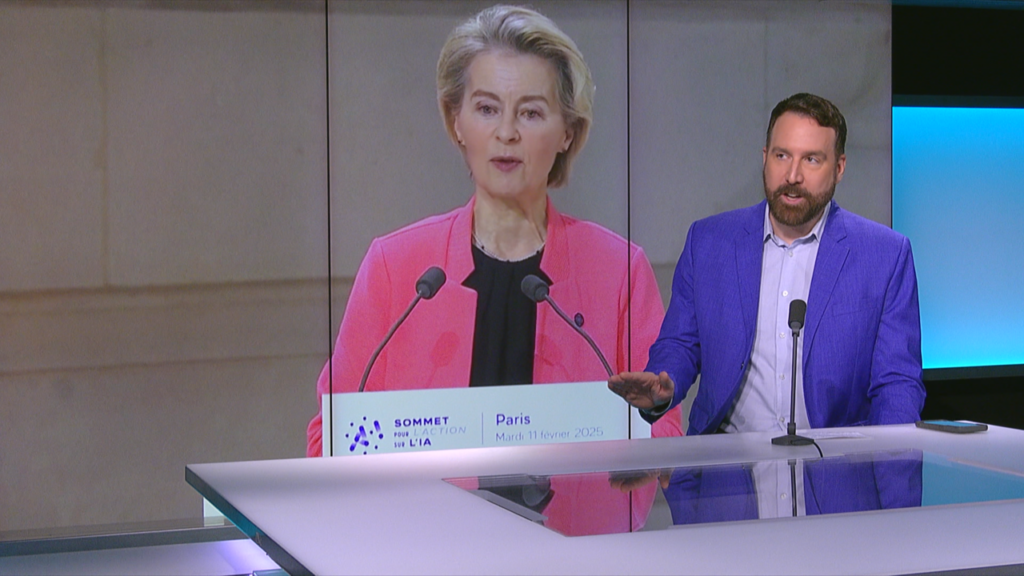

Moreover, questions arise about the geopolitical forces that have triggered the shift. As the FRANCE 24’s Brussels Correspondent Dave Keating mentioned this week, the EU officials cannot escape the questions about how much hard Washington push might have been for a different regulatory approach—especially as the US is making a race for the future of AI standards to secure its influence.

At this moment, the Commission is holding on to the view that its effort is not deregulation but updating. They maintain that the EU digital regulations, which were mostly designed almost ten years ago, need to adjust to rapidly evolving tech. The next few months will indicate whether this reasoning is sufficient to convince the European Parliament and national governments, who both have the authority to give the green light to any legal changes.

The point that is already clear is that the talk about Europe’s digital future – its principles, its competitiveness, and its determination to stand up against the most influential tech companies in the world – is not over yet.